[Val here. I write nearly all of our blog posts, but since Stan’s been researching in the aftermath of our recent passage, it’s only appropriate that he write this one. You’re in for a rare treat! By the way, I argued that the title be “To Hell in a Handbasket,” but that only launched us into a tangential yet animated discussion on the nature of handbaskets, and why is that even a word anyway… so here we are, with Stan’s classier and more descriptive heading.]

The Tasman Sea lies between New Zealand and Australia. We’ve crossed it three times in two different boats, and each time it has demonstrated why it is among the top five notoriously difficult and dangerous seas in the world. Our recent crossing in March 2019 was supposed to be our easiest, but we ended up seeing the largest waves we have seen in over 36,000 miles of cruising in the past ten years. And it humbled us.

For you, our readers, let me begin by saying that this post will have some technical sections, so if you are looking for pretty pictures and exotic places, read one of Val’s other posts. Because we have over 2,000 people subscribed to this blog, most of whom we don’t know, we believe we should post some material of interest to blue water cruisers. So here’s the story about how we were caught by a nearly vertical 25 foot wave directly on our beam and why we never want that to happen again. This is also a story about the risk of getting complacent and overconfident, and how the ocean will almost always make you pay if she finds you in that state of mind.

The 1100-mile route from the northern tip of New Zealand to Sydney, Australia took us on a line due virtually straight west. The forecast from Whangarei to Sydney looked favorable, and our weather router gave us a hearty thumbs-up. Mild winds (10 to 20 knots) and following seas for the first four days, with some increase in wind to 30 knots on only part of the last day, shifting to the north and hitting us directly on our starboard beam. Beam wind and seas are normally fine with us because the FPB design gives us a good ride in all directions. That combined with our ability to maintain a speed of about 10 knots in all conditions adds a measure of safety that we appreciate every time we venture offshore.

Sea state also looked good to us with waves, even during the last 24 hours approaching Sydney, predicted at 4-6 feet, again on our starboard beam and fairly normal for us on a long passage. Our weather router told us to expect current from various directions up to 1.5 knots.

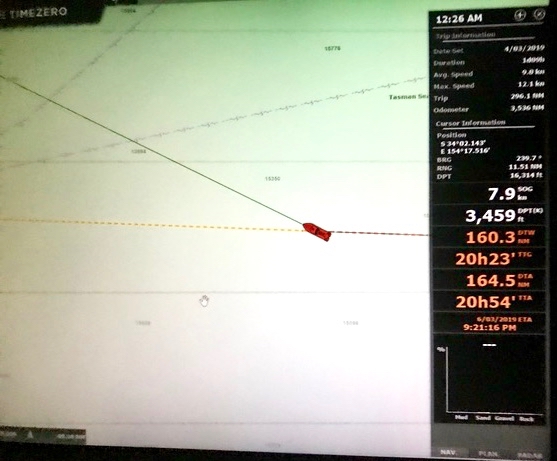

But around halfway through our 5-day passage, the barometer dropped a few points and our forecast began to change. Around 160 miles from Sydney, our speed slowed from our normal 10 knots to 6-8 knots, and our boat position on the chart plotter showed us crabbing severely. In the image below you can see that we are pointing north about 30 degrees off our course over ground.

This is the effect of ocean current on our boat speed and direction. At the time, we noted the current, and our reaction was annoyance, because the current was slowing our speed substantially and threatening our plan for a daylight arrival in Sydney at the end of a long voyage. This was a huge mistake on our part, because in retrospect we knew that current mixed with wind can create unpredictable and nasty waves; this is the complacency part of the story.

The situation then deteriorated further. Soon after this picture was taken, the orientation of the boat on the chart plotter changed to where our boat heading was about 45 degrees SOUTH of our course line. The current direction had changed and was now coming from the south. Our speed dropped to as low as 6 knots. 4 knots is major ocean current, and still we did not put the pieces together. We knew that the wind would build to 30 knots on the last day and that it would be from the north. Duh, wind from the north and current from the south should have told us that trouble was ahead, but we underestimated the Tasman Sea; this is the overconfidence part of the story.

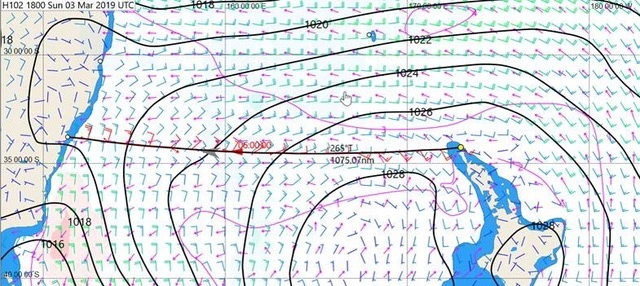

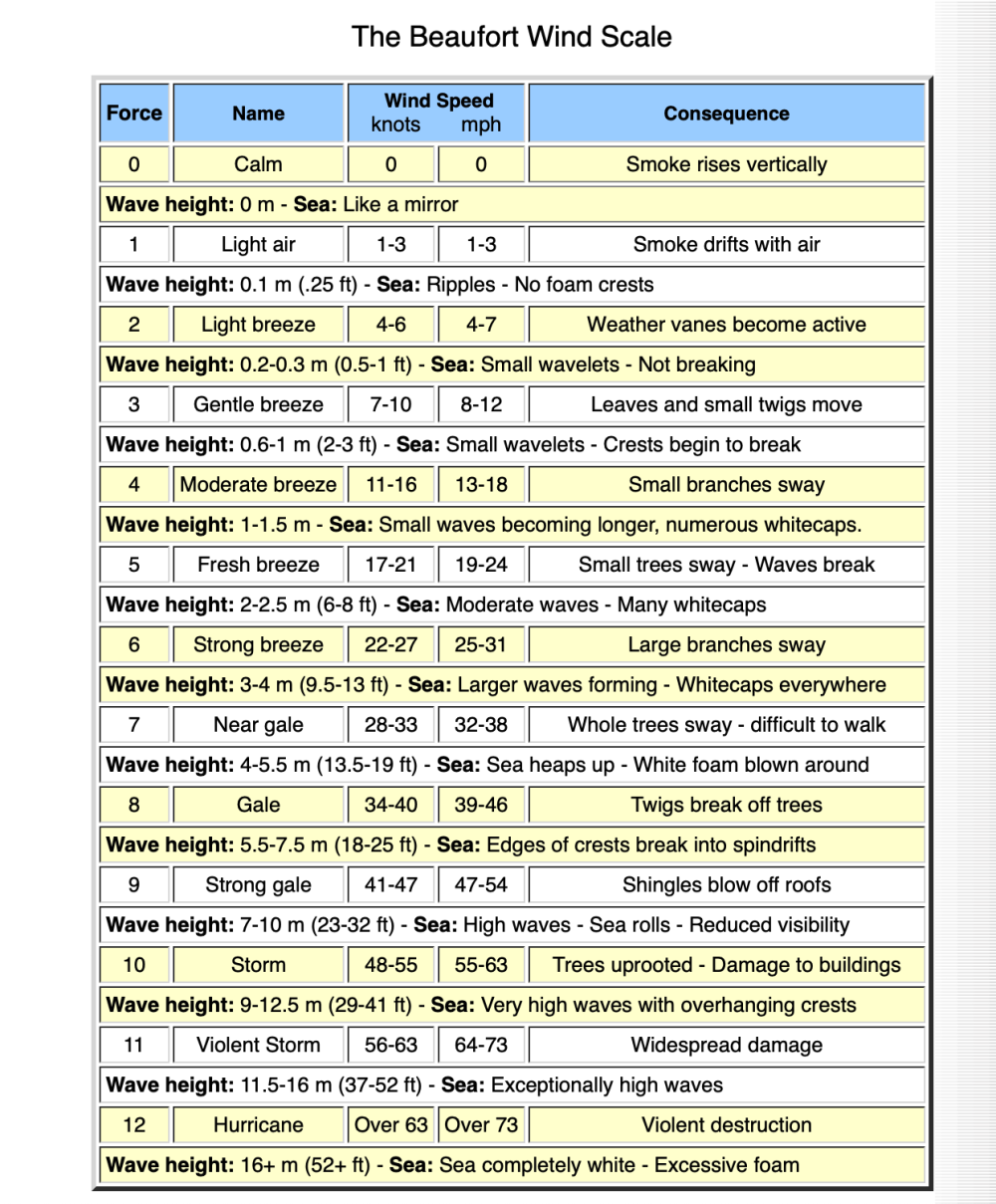

Mariners use the Beaufort Wind Scale to predict wave height. It’s been around for a long time and is a mathematically accurate tool. Winds on our last day were predicted to be 30 knots. Using the scale, we should have anticipated waves of 13-19 feet. See Force 7 below.

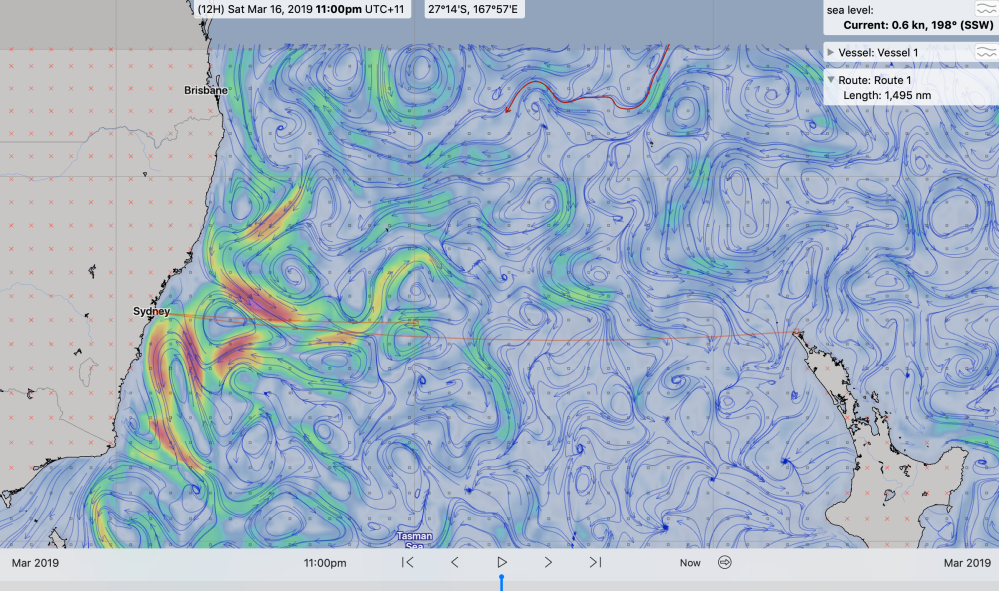

We’ve been in 30 knot winds before; in fact, on our first crossing from New Zealand to Fiji we encountered winds of 40 knots and large waves, but these were not affected by current, so we rode up and over them easily. The reality is that despite a lot of time on the water, we rarely encounter significant ocean currents, largely because we just have not been to areas where they are common. The Tasman Sea is different. It has a major current called the Eastern Australian Current that flows predominantly north to south along the southeast coast of Australia. Our previous Tasman crossings were north of this area, so this passage was our first encounter with this current. Below is a map showing the current on the day AFTER we arrived in Sydney. We did not have this information during the passage, which is another major error on our part and a function of not using all the available information at our disposal.

It is worth pointing out that the direction of the currents is quite variable and that the red zones are speeds up to 4 knots. Note that our path took us directly through the worst zones.

As with most stories about things that go really wrong, there were other factors that contributed to our meeting with a monster wave. Taken alone they would be annoying, but when put together in the right combination and in the right sequence the result can be more than the sum of the individual parts. So being a moonless night, the end of a five-day passage, Val being sick and unable to take the helm and me being at the helm for 12 hours all contributed to us continuing on a westerly course with waves on our beam opposed by current from the opposite direction. [Yoo-hoo, note from Val here. Isn’t he sweet to say I was “sick?” That way you picture me off barfing someplace, which OK, isn’t very attractive, but can happen to anyone, right? The reality is that once we started on Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride in the middle of that black night, I was anxiety-ridden and incapable of standing my solitary watch. I stayed in the great room with Stan, bringing him food and drink and whatever else, in between sucking my thumb in fetal position on the settee and avoiding looking at the white foam snaking ominously past our windows at eye level. Now back to your regularly scheduled programming.]

We could tell by the boat movement that the waves were big, but we could not see them in the dark. Even with the forward flood lights on, we did not appreciate just how bad things had become. When the sun finally began to rise, we were surprised at the sea state around us and finally started to alter our course. We headed south so that the swell was behind us, then later aimed more northerly and jogged over the big waves. One of the most confusing parts of this story is the way the sea would suddenly settle down and have us thinking the worst was behind us, only to build again dramatically. In retrospect we realize this was due to our transiting areas with less current, but at the time we did not appreciate this. As the waves settled in these areas, we turned westerly again towards Sydney because we were tired and wanted to get to safety as soon as possible. It was during one of these periods back on our original course that I looked to starboard and saw a large wave approaching directly on our beam. For all of the reasons noted above, we continued on course as we watched the wave approach. Suddenly, with the wave about 50 yards from the boat, it combined with a wave from a slightly different direction and the manageable 15-foot wave became a 25-foot wall of water, nearly vertical and ready to break. We did not have time to turn into this monster and it hit us directly on the right side. As the Buffalo started up the wave face, she listed to the side as far as we’ve ever experienced and at the top, I just waited to see which way we would fall. Luckily for us, we proceeded over the back of the wave.

So, what did we learn and what do we now understand better? We knew that wind wave height is dependent on wind speed and direction, fetch, ocean bottom depth and contour and current. We appreciate now that when wave peaks combine, they are 100% additive, meaning that two 10-foot swells meeting with their peaks in sync will result in a wave 20 feet high. We understand that opposing current is more dangerous than prior experience had taught us, and current evaluation and monitoring in the future will be a bigger part of our passage planning.

If our course puts us in an orientation with increased risk, we will change course earlier in the future, especially in any condition where the wind speed is greater than 30 knots.

This recent ocean crossing also caused us to go back and rethink what we now know about waves and currents and apply it to our own boat:

- Weather reports of “significant wave height” that mariners routinely use are the mean of the highest 1/3 of waves.

- We know that mixed in with these seas will be periodic waves twice as high, and it is not unusual to encounter these large seas as often as every 4-12 hours. Looking at the Beaufort Scale above, that means in the same Force 7 conditions we experienced, we can EXPECT to see waves as high as 26-38 feet. This means that the concept of “rogue waves” is obsolete.

- We will never again look at 30 knots of wind as “no problem.”

- Major currents contain lots of eddies that can change speed and direction frequently and be well outside the predicted current path.

- Opposing current and wind makes seas higher and steeper.

- Steeper waves are more dangerous because they can break.

- To capsize a boat, the wave must be breaking.

- A wave will break if its wave length (peak to peak or trough to trough) is less than 7 times its height. In other words, a 10-foot wave with a wave length of less than 70 feet will break.

- It is difficult to estimate wave height or length from inside a boat.

- The position of the boat relative to the wave determines the risk inherent in a breaking wave. Stern or bow to the wave face are the safest orientations, beam to the wave face is the most dangerous.

- Resistance to capsize goes up exponentially with boat size.

- Research models show that many boats will capsize when breaking waves reach a height of 30% of boat length. At a wave height of 60% of boat length, any boat can capsize.

We can conclude from this that Buffalo Nickel met two of the three criteria needed to capsize: beam-to orientation and wave height greater than 30% of boat length; however, the wave that hit us was not breaking. We were very fortunate. We believe, since the wave face was almost vertical, the wave was very close to breaking. Our boat design improved our risk profile, as FPB’s are designed and built with all of the above considered. Working with our boat’s designer Steve Dashew after this episode, we concluded that we were probably heeled over to about 35 degrees. The boat’s stability curve peaks somewhere in the 75 to 95-degree range, thus we stayed upright. Even knowing this, we never want to meet a wave like this again. And we will never again get complacent or assume we are safe just because we have the best boat in the world. The sea does not care.

For further reading on waves and current, we refer you to:

Attainable Adventure Cruising at morganscloud , and SetSail

One of the few good things about our passage was that it provided a dramatic real-world test for our new steering design, which performed admirably. We know we’ve left you hanging on that issue, and we will publish another post on the solution very shortly.

Stan and Val

Congratulations on your crossing….notwithstanding the weather welcome Australia provided. Unfortunately, our Met Bureau (BOM) sea current data is not so well known. You really hit the hot spot! But good to get a better feel for stability and the strength of your boat.

I am interested in your night time experience with the bow lighting and sea state. Is there a better way to set up the lights? Or are more powerful lights the solution? Or is the problem more fundamental… to the steering position from inside the main cabin?

regards

Anthony Baird

Hi Anthony,

Thanks for the question, I have not fully thought through what I’m doing about the lights, but here is my latest thinking. Maybe someone else reading this blog can comment about their experience with lights.

We have 6 lights on the forward mast: 3 Rigid Industries Q series Driving Pro LED (#544313) each with 19,000 lumens and 3 Rigid Industries Q series HyperSpot LED (#544713) each with 7,000 lumens. The HyperSpot lights are too small and I plan to replace them with the Driving lights. I would like to add two side lights and one big one aft to illuminate the entire area around me.

I have never understood why we drive blind at night. I understand the issue of night vision loss, but I am willing to loose it in order to asses sea state, especially if I’m offshore. Some people say they can see white foam on a moonless night, but I can’t.

Stan

I remember running in huge seas, survival conditions. I didn’t have lights but the moonlight helped me to see the frothy white stuff. In those conditions lights on the bow would have been only a little help. Pointed astern is really what was needed. Do you have such mounted on your boat?

Yes, we have aft-facing lights but I hadn’t thought of using them as a primary source of orientation. Will do next time we are in big seas to see how that helps. Thanks for the suggestion.

Hi, you two!!! I am so glad you are ok. Sounds like your Angels & ancestors were keeping an eye out for you.

Much love!

Erin

Hi! I needed you a few weeks ago……Got a haircut that will last 6 months! Hoping to see you for a visit in Japan. We leave Sydney tomorrow and start the trek to Raja Ampat, Indonesia.

Hi Stan and Val,

Thank you for this update and sorry to hear about your harrowing experience. As you said, good to know the boat is working well.

I think that part of your tool-set is a FLIR night-vision camera. This didn’t help with surveying the waves?

Going by the screenshot, you changed navigation software from Coastal Explorer to TimeZero? Can I ask what drove that change?

Hi Carl,

We actually have a FLIR night-vision camera and use it, but in this instance I simply did not think about it. It’s fascinated my how that happened during this episode because we really find the FLIR a useful aid for sea state evaluation and especially in anchorages at night where we know there will be at least one boat without an anchor light on. I can only say that fatigue is my most believable excuse. Val and I normally do 4 hour on/4 hour off shifts when underway, and I had been at the helm for more than 12 hours when this all started because Val was not able to assist. We find 4 hours is about the maximum we can be in command and still be effective if anything is happening. After 4 hours of playing hearts on the iPad, I know I take the queen a lot more than I did at the beginning of my watch. It did not cross my mind to turn on the FLIR: lesson learned.

You are correct, the picture shows TimeZero, which we use on the new boat. We still have Coastal Explorer running as a backup, and we still like it very much. On our 64 we used CE as the primary and ran Furuno NavNet as the backup. TimeZero integrates the plotter, sounder and radar well, so that’s why we are trying it as the primary now.

Stan

welcome to Sydney Val and Stan, I hope your stay is more enjoyable than your journey here.

Thanks for a great write up!

Scotto

Thanks Scotto,

We are enjoying Sydney, what a beautiful harbor area. And the surrounding communities tied to the harbor are spectacular. That said, we are anxious to get on our way to Raja Ampat and then Japan. We hope to be in Japan by May.

Stan

are you swinging off the pick, or slotted in a Marina?

I’m up the Parramatta River at Cabarita Marina.

If You are close by, I’ll swing past for a look.

Can I suggest Centre point tower for a good bistro in a revolving restaurant,

with the best views to Newcastle, Wollongong and the mountains(at night) in good weather,

might have trouble seeing the next roof in todays muck though.

cheers

Scotto

Very good observations. Well done on learning without drowning!

Stan and Val:

We enjoyed reading and learning from your recent post. Our Nordhavn 47 is currently stored at Southwest Harbor Maine and we are looking forward to getting back aboard and cruising the Canadian Maritimes this summer. In case you forgot, we met you in Mexico several years ago when we were aboard our Island Packet 420.

All the best,

Wytie and Sally Cable

Wytie and Sally,

We remember you well and the dinner we had during that major storm in Barra. We follow your blog as well.

Stan and Val

Thank you for a really well written and informative article.

The monsoon season here in East Africa has recently swung from NE to SE and with it we get increased winds and the Somali current heats up and is a major reason for our seasonal fishing and sailing.

In a recent small boat fishing competition we encountered similar ( but in much smaller shorter seas ) sea state variations that caused me to think of a reason. I was sailing a 43 ft Jeaneau sloop whilst most fishermen were in the 20 -28 ft motor boats.

I now understand the current eddies off the structures were causing the variations. Wind over current and wind with current. Thank you for this.

Hi Peter, Since writing this blog entry, we had another experience with eddies, this time as we rounded Fraser Island in Eastern Australia. The seas would build and then settle down as we passed through various areas of differing currents. At times it was dramatic. Safe travels!